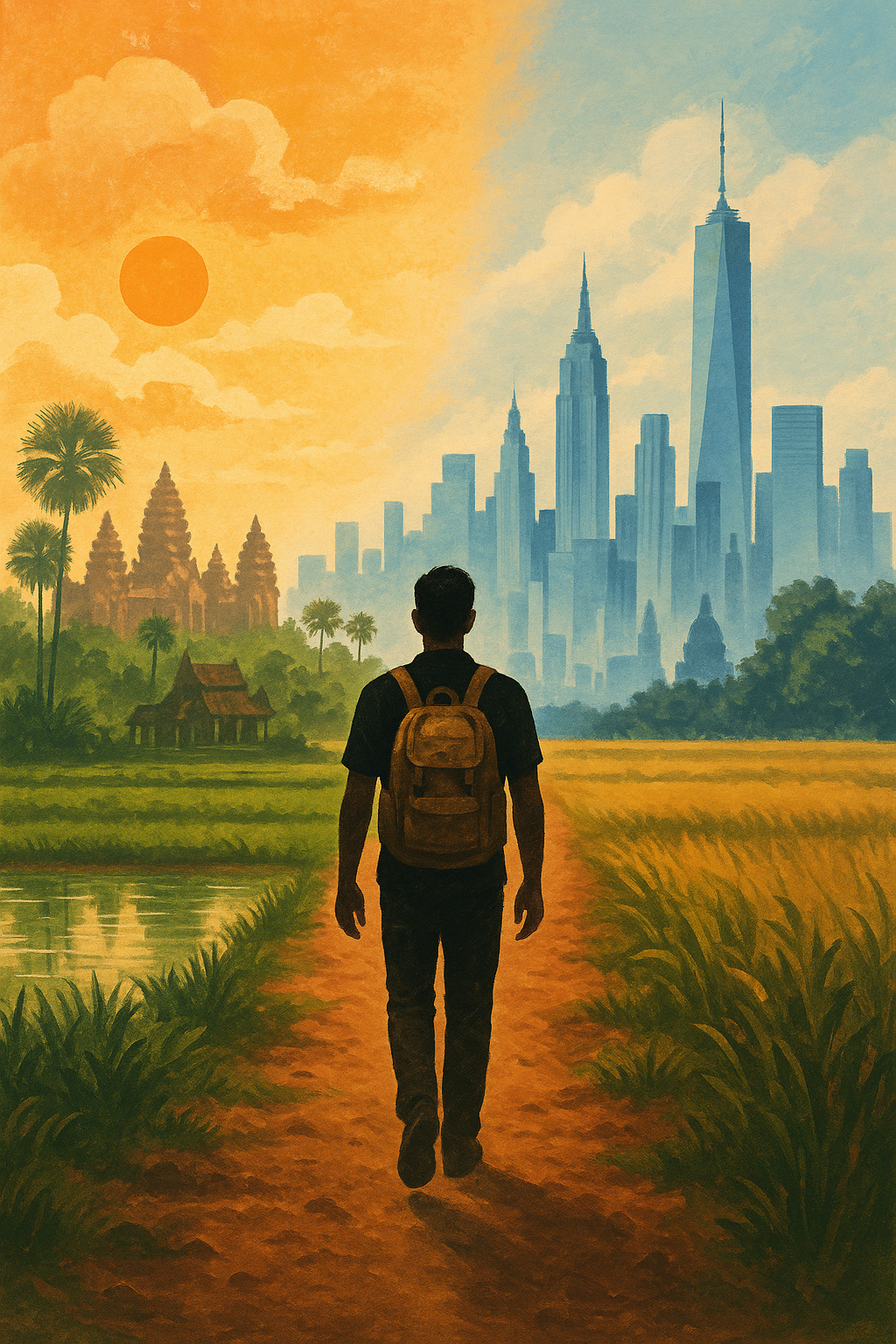

Memoir excerpt: Arrival

We arrived in Lynnwood with nothing but memory pressed to our backs, the ache of what could never return, and a hope so fragile it barely had a name. Cambodia was behind us, at least the physical borders of it. But its shadows traveled with us in our posture, in our silence, in the way we measured every new kindness with caution. We brought Cambodia in the way we carried ourselves, in the rhythm of our speech, in the quiet vigilance that never quite left the body. Lynnwood was nothing like the world we had left, and nothing like the idea of America we had been promised. It was not golden or gleaming. It was gray. A quiet place where strip malls met mossy rooftops, where old evergreens outnumbered neighbors, and where people did not look at you long enough to ask questions.

Back in the early 1980s, Lynnwood still felt like the outskirts of somewhere else. Seattle was the city, Everett the place of mills and labor, but Lynnwood was in between, a waiting room of a town. Rows of low-slung apartments, wet pavement slicked with moss, drive-through teriyaki joints that seemed to multiply on every corner, and the constant hum of traffic along Highway 99. It was a place that did not demand much, and in that way, maybe it offered more than we understood. For a family that had survived being told to disappear, to erase ourselves for the sake of survival, the anonymity of Lynnwood was its own kind of mercy.

We moved into a small apartment built more for utility than comfort, perched above a narrow concrete staircase slicked with snow and ice. My mother remembers the day we arrived like a blur edged in cold and white. Snow was falling, soft and slow, like ash. It was the first time she had ever seen it.

In Cambodia, the seasons had been hot, wet, or bone dry. There had been monsoon rain that soaked through everything, scorching heat that cracked the fields, and drought that stole the color from the land. But never snow. There was no roadmap for what to wear in this new world, no cultural manual for cold. She wore flip-flops because that was what she had. A habit carried from one continent to another, unfit for this new world of ice and concrete.

As she climbed the narrow staircase to our apartment, arms wrapped tightly around my small, wriggling body, snow fell in slow spirals around her like a soft warning, gathering in quiet drifts on each step. She did not know what black ice was, had not yet learned how winter hides its danger in silence. Her foot slipped. Her body jolted sideways, gravity yanking her from the unfamiliar footing of this foreign place.

We fell as one. Her arms tried to catch me, protect me, but the world moved faster than love could react. My face met the edge of a concrete stair with the brutal finality of impact, skin splitting on contact, blood blooming bright against the white powder. The sound of my cry was lost in the gray sky above, muffled by snowfall and fear. That wound, jagged and vivid, was my first imprint on American soil. Not a name. Not a language. A scar.

And it never left.

That moment became part of the family lore, a story told carefully, sometimes with guilt and sometimes with quiet acceptance. As a kid, I hated my scar. I hated how it made me feel marked, how it seemed to draw eyes and questions I did not want to answer. I hated that no one else had one quite like it. I envied the smooth-faced boys in school, the ones whose skin held no history, no explanation, no accident written into their flesh. To me, the scar was not just an accident. It was a reminder that I did not quite belong, even if I did not yet have the language for it. It felt like a badge of shame, a permanent sign that I had entered this country clumsily, that even my first steps into America had been flawed.

Years later, when I was old enough to ask, my mother told me the story of that day. Her voice was even, not defensive or emotional, just honest. She described the snow, the feel of it under her feet, the way it sparkled like salt, and how utterly unprepared she was for what it could do. “I did not know,” she said. “How would I know?” That fall, that scar, that moment, it was not carelessness. It was learning. It was survival in a new form. And once I saw it through her eyes, the shame began to dissolve.

What remained was something different, a strange kind of pride.

Because scars, I came to learn, are not marks of failure. They are proof. Proof that we have endured. Proof that we were broken or bruised, and that we healed, even if imperfectly. That scar on my right cheek is not just a remnant of a winter fall. It is part of our arrival story. It is my mother, barefoot in the snow, doing the best she could to carry both of us into a future none of us could yet see.

For my parents, Lynnwood was a place of subtle contradiction. Safe, but unfamiliar. Calm, but isolating. The streets were lined with towering fir trees and sagging power lines, apartment complexes with names like “Forest Glen” and “Pinewood Court,” the kind of places that offered proximity to a better life without ever promising one. The air always smelled like rain, like wet earth and diesel exhaust. There was a certain kind of quiet there, almost too quiet, especially for people like us who had lived with the constant rustle of fear, the ever-present noise of survival. It was the first time we were no longer hunted, no longer starving. But peace is not the same as belonging, and we still did not know what it meant to be home.

The apartment itself was small, a box stacked on top of other boxes, each one filled with families like ours, immigrants from places most Americans could not pronounce. The walls were thin enough to hear neighbors argue or laugh, to catch the smell of garlic frying or soup boiling. We learned the rhythms of other people’s lives before we learned their names. There was comfort in that closeness, a reminder that though we were far from where we had begun, we were not alone in beginning again.

Every detail of that first winter etched itself into my parents’ memory. The radiator that hissed and clanked at odd hours, sometimes hot enough to burn if you touched it and sometimes silent when you needed it most. The carpet, scratchy and stained, that smelled faintly of mildew. The single window that looked out onto the parking lot, where cars sat under blankets of snow, their edges softened, their identities erased. The walk to the bus stop, where we would stand shivering in too-thin jackets, our breath puffing out in clouds, wondering if this was what progress looked like.

My father said little during those first months. He kept his head down, took whatever work he could find, rarely spoke about the past, and never speculated about the future. He was a man who had already seen too many futures erased. My mother carried the weight in other ways, cooking rice on a borrowed hotplate, figuring out food stamps and English words she would mispronounce but never stop trying to learn. She wore her survival on her back but never asked us to carry it. We were the new generation, she said. We would go further. Do better. Speak without shame.

In Cambodia, even during the worst years, there had been a certain familiarity to their movements, a way of knowing how to read the landscape, how to move through danger. Here, every gesture seemed more cautious, every decision tinged with uncertainty. Buying groceries was not just shopping, it was translation, calculation, negotiation with a system that was at once indifferent and intimidating.

They discovered Safeway with its aisles that seemed endless, its lights too bright, its produce gleaming under misting sprays of water. My mother held a bottle of mayonaise as if it were a puzzle, turning it in her hands, uncertain what it was or how to apply it. She stood in front of rows of peanut butter jars, overwhelmed by the abundance of a single product that she had never seen before. Choice itself became a burden, a reminder of how little we knew.

Yet slowly, life began to take shape. They learned which bus routes to take, which thrift stores had the cheapest clothes, which neighbors were friendly enough to exchange a nod in the parking lot. My father found steadier work. My mother began to string together sentences in English. My brother and sisters began to mimic words, hesitant at first, then bolder. And the scar on my cheek faded from angry red to pale pink, a constant companion but less loud.

Lynnwood did not ask questions. It did not welcome us loudly or tell us we belonged. But it let us exist, and maybe that was enough for a beginning. In the stillness of its gray mornings and moss-draped roofs, we began to rebuild, not as the people we had been, but as the people we were becoming.

And, now, every time I trace the scar on my cheek with my fingers, I remember that this life, our life here, did not begin with a celebration. It began with a fall. A mother’s misstep. A child’s cry. The shock of snow. And the stubborn decision to get back up again.

We were not yet home. But we had arrived.