The Death of Grit

Last weekend, I stood at the edge of a soggy soccer field, watching my daughter’s team warm up under gray skies. The drills were basic: footwork, passing, shots on goal. But halfway through, I saw her slump her shoulders after missing a save, then glance toward the sideline to see if I had noticed. I did. What I saw wasn’t just frustration—it was a quiet unraveling. Not because she didn’t care. But because she did. And because caring without immediate success is one of the hardest emotional weights to carry at her age.

I walked over during the break, knelt next to her, and asked how she was feeling. “I’m just not good at this,” she said. “It’s too hard.” That’s when it hit me: she wasn’t struggling with technique—she was struggling with struggle itself.

Chapter 4: Khao-I-Dang (1980)

I was born in a soldier’s camp.

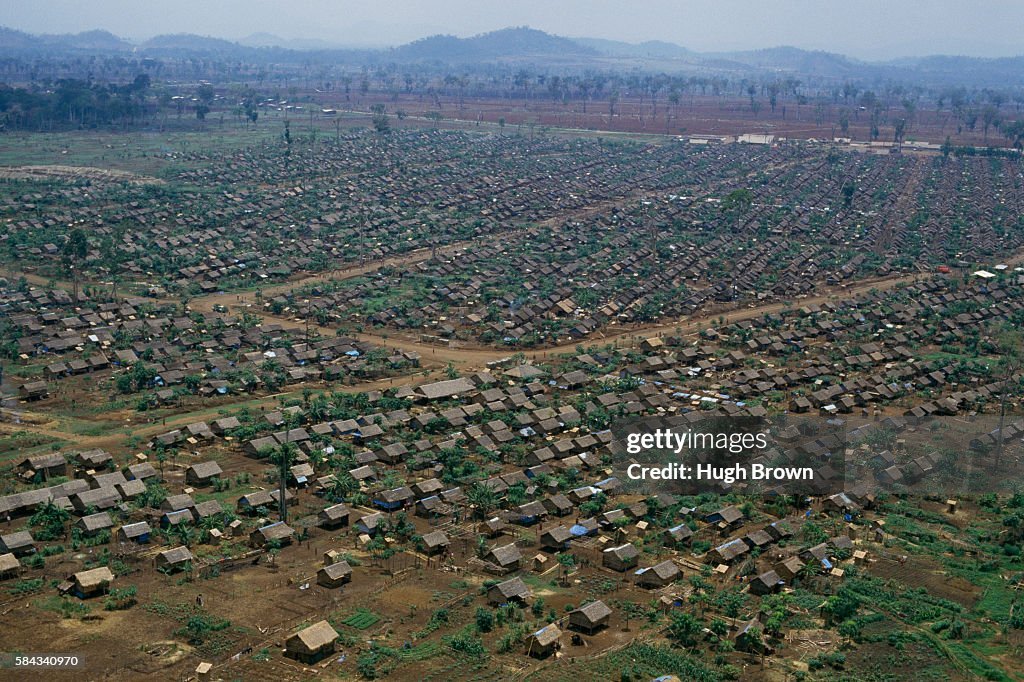

Khao-I-Dang was not meant for beginnings. It was built for overflow, for those who had nowhere else to go. Established in late 1979, just across the Thai-Cambodian border in Sa Kaeo Province, it spread across the land like a nervous system, pulsing with fear, hope, and motion. By the time my parents arrived, the camp had become the largest and most enduring refugee center for Cambodians fleeing both the Khmer Rouge and the Vietnamese invasion.

Each house was meant to hold one person. But the rules folded under the weight of survival. The camp swelled far beyond its intended capacity. At its peak, over 160,000 people were crowded into a space meant for far fewer. What had once been forest became a dense city of tarps, bamboo poles, barbed wire, and dust. There were designated sectors for food, sanitation, registration, and hospitals, each a fragile attempt to impose structure on chaos.

It was there, in a crowded medical post run by international aid workers and Thai soldiers, that I entered the world.

My mother’s labor began sometime after two in the morning. The air was thick and unmoving, heavy with heat that lingered through the night. The pain gripped her in waves. She was not alone when the contractions came. My father walked beside her, steadying her as wave after wave of pain coursed through her body. The path to the clinic was uneven, lit only by flickering lanterns and the dim outline of the moon. My mother gripped her belly in one hand, her other hand clutching his arm, each step more fragile than the last. My father tried to encourage her, his voice quiet, his pace slow. But she couldn’t keep walking. Her legs gave out halfway there, and she collapsed at the edge of a dirt path, breathless and afraid.

A security vehicle making its night patrol found her there. The soldier didn’t speak Khmer well, but he understood what he saw. He carried her into the vehicle and drove quickly through the maze of sleeping shelters and dimly lit checkpoints. The vehicle passed the UNICEF trucks, the Red Cross tents, and the narrow rows of shacks built from relief materials. The camp was quiet, but her breath and heartbeat were loud.

Chapter 3: The Disappearance of Names

In the new Cambodia, names became a threat. Not the ones given at birth, but the ones that carried memory—teacher, soldier, merchant, student, doctor. Titles became targets. Histories became crimes.

So my parents disappeared their pasts. My mother, who had once moved with confidence through the rhythms of Phnom Penh, took on the stillness of someone trying not to be seen. My father, who had learned to read before he could tie his shoes, stopped speaking in full sentences.

“To survive,” my father told me, “you had to forget who you were. You had to forget that you remembered.”

Names were the first to go.

My father, once the proud eldest son of a large family, stopped hearing his name spoken aloud. His sisters called him “Bong,” the Khmer word for older brother—but even that faded. The risks were too high. The more you cared for someone, the more dangerous it was to be connected to them. Love had to be camouflaged. Intimacy had to be disguised as indifference.

What We Built, What We Lost

There are places that shape us. Not because they’re perfect, but because they let us show up as we are, and do work that matters. For me, the Defense Digital Service was that place.

I joined DDS because it wasn’t like the others.

My time at DDS wasn’t defined by a single project — it was a blur of missions stacked on top of each other, each demanding urgency, clarity, and heart. I worked on everything from counter-unmanned aerial systems (cUAS) to critical efforts tied to the Afghanistan evacuation. When the team needed support on recruiting, I stepped in there too — because at DDS, titles didn’t box you in. If something needed doing, you did it.

It was a flat organization — no hierarchy to climb, no corner office to covet. Everyone held the same title. No one was angling for a promotion or polishing their résumé for the next big job. We were time-bound — temporary stewards of a mission that would continue after us, if we did it right.