Memoir excerpt: The Strength of Her Back, the Tenderness of Her Hands

America moved fast. It assumed fluency. It demanded adaptation.

My mother became a nanny. Not because it was easy, but because caring for children was the one skill she carried across oceans and borders. She couldn’t read or write English. Not because she wasn’t intelligent but because survival had never afforded her the time.

“All I knew,” she once told me, “was how to take care of kids. So I did that. And I prayed you’d have more.”

She folded laundry, warmed bottles, braided hair that was not her own. She did not complain. But she did watch. She paid attention to everything. She protected us in ways that no curriculum could ever teach.

Her life wasn’t measured in degrees or promotions. It was measured in the strength of her back and the tenderness of her hands.

Why Term Limits Should Be the Norm for Government Innovators

I’ve seen this problem from nearly every angle.

At the Defense Digital Service (DDS), I built tools side-by-side with warfighters whose lives depended on getting it right. Later, standing up the Customer Experience Office (CXO), I helped craft enterprise strategy and policy across sprawling federal systems. Outside government, I served as a general manager at Rebellion Defense, and now as an advisor to MO Studio, supporting mission-driven design and technology teams working in complex public environments.

Through these experiences, one truth stands out:

The department suffers from a lack of motion.

The Death of Grit

Last weekend, I stood at the edge of a soggy soccer field, watching my daughter’s team warm up under gray skies. The drills were basic: footwork, passing, shots on goal. But halfway through, I saw her slump her shoulders after missing a save, then glance toward the sideline to see if I had noticed. I did. What I saw wasn’t just frustration—it was a quiet unraveling. Not because she didn’t care. But because she did. And because caring without immediate success is one of the hardest emotional weights to carry at her age.

I walked over during the break, knelt next to her, and asked how she was feeling. “I’m just not good at this,” she said. “It’s too hard.” That’s when it hit me: she wasn’t struggling with technique—she was struggling with struggle itself.

Chapter 4: Khao-I-Dang (1980)

I was born in a soldier’s camp.

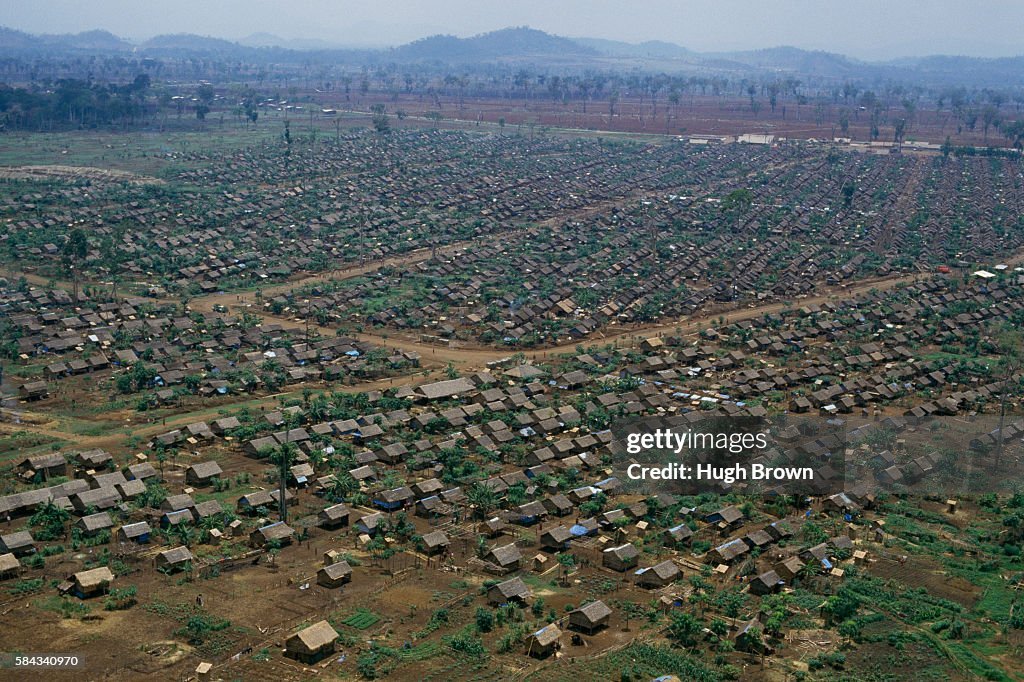

Khao-I-Dang was not meant for beginnings. It was built for overflow, for those who had nowhere else to go. Established in late 1979, just across the Thai-Cambodian border in Sa Kaeo Province, it spread across the land like a nervous system, pulsing with fear, hope, and motion. By the time my parents arrived, the camp had become the largest and most enduring refugee center for Cambodians fleeing both the Khmer Rouge and the Vietnamese invasion.

Each house was meant to hold one person. But the rules folded under the weight of survival. The camp swelled far beyond its intended capacity. At its peak, over 160,000 people were crowded into a space meant for far fewer. What had once been forest became a dense city of tarps, bamboo poles, barbed wire, and dust. There were designated sectors for food, sanitation, registration, and hospitals, each a fragile attempt to impose structure on chaos.

It was there, in a crowded medical post run by international aid workers and Thai soldiers, that I entered the world.

My mother’s labor began sometime after two in the morning. The air was thick and unmoving, heavy with heat that lingered through the night. The pain gripped her in waves. She was not alone when the contractions came. My father walked beside her, steadying her as wave after wave of pain coursed through her body. The path to the clinic was uneven, lit only by flickering lanterns and the dim outline of the moon. My mother gripped her belly in one hand, her other hand clutching his arm, each step more fragile than the last. My father tried to encourage her, his voice quiet, his pace slow. But she couldn’t keep walking. Her legs gave out halfway there, and she collapsed at the edge of a dirt path, breathless and afraid.

A security vehicle making its night patrol found her there. The soldier didn’t speak Khmer well, but he understood what he saw. He carried her into the vehicle and drove quickly through the maze of sleeping shelters and dimly lit checkpoints. The vehicle passed the UNICEF trucks, the Red Cross tents, and the narrow rows of shacks built from relief materials. The camp was quiet, but her breath and heartbeat were loud.